Islamic radical conservatism in Iran, dominant in government for the past two decades, has revealed its dangers through "purification" efforts, an adventurous foreign policy, erosion of the middle class, and the weakening of the private sector.

After two decades of alienating the majority of Iranians—leading over 61% of eligible voters to abstain from the June 2024 presidential election—some within the system now appear to be considering a revival of pre-2005 traditional conservatism.

A report from the centrist website Entekhab noted on Wednesday that the current structure of Iran’s conservative camp appears disjointed, especially after their defeat in the July presidential election, which saw the election of non-factional candidate Masoud Pezeshkian with the backing of “reformist” groups.

Since the disputed 2009 election, which secured ultraconservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second term, conservatives have attempted to present a unified front ahead of every parliamentary and presidential election. However, these attempts repeatedly fractured, and if not for interventions from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the Guardian Council, the reformist camp might have reclaimed power.

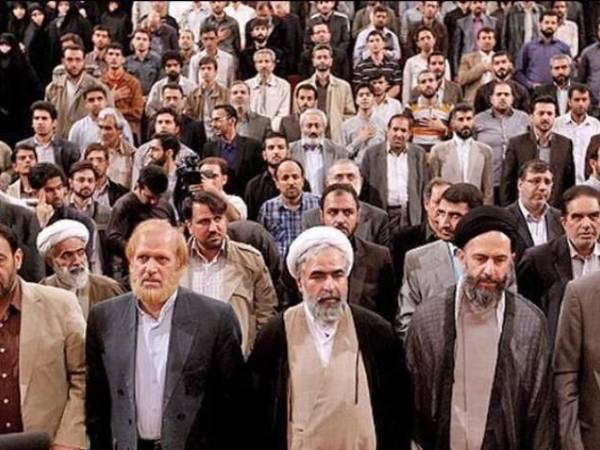

This infighting has steadily diminished the conservative camp, particularly over the past 11 years since pragmatist Hassan Rouhani’s presidency. What remains is a core group of 100 to 160 ultraconservative politicians, primarily linked to the Paydari Party, who advocate for a non-democratic Islamic government rather than the Islamic Republic's semi-democratic structure.

Their ranks have now dwindled to fewer than 80 parliament members and a handful of others in appointed roles, such as those in the Expediency Council.

According to Entekhab, “moderate” conservatives now hold the upper hand in Iranian politics, with Majles Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf leading efforts to restore the conservative camp to its pre-2005 stance. The report noted that Ghalibaf has actively worked to limit the influence of Paydari members within the Majles.

This narrative, however, is questionable. To secure his role as Speaker, Ghalibaf maneuvered between Paydari members, other conservatives, and a few pro-reform MPs, ultimately winning the position with votes from the latter. By spring 2024, Paydari had dwindled to just over 60 members, marking one of its lowest points in popularity and membership.

President Pezeshkian disclosed on the day of the Majles vote for his cabinet in August that it was, in fact, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei—not Ghalibaf—who ensured that all ministers received the necessary vote of confidence from parliament.

Over the past 20 years, especially during Ahmadinejad's presidency, hardliners succeeded in sidelining many moderate conservatives, including former Majles Speaker Ali Akbar Nateq Nouri. In recent years, they have also marginalized other influential conservatives, such as the Larijani brothers—former Chief Justice Sadeq Amoli Larijani and former Majles Speaker Ali Larijani—as well as former President Hassan Rouhani and nearly all of his "pragmatist" allies.

Now, as the country's economy is in its weakest point, the public, as well as politicians in Iran are beginning to remember what Ahmadinejad and the Raisi administration have done to a better economy that existed in Iran until 2005.

Ahmadinejad’s presidency brought sanctions, international isolation, and squandered a massive windfall from soaring oil prices, leaving the treasury depleted by 2013. According to President Pezeshkian’s reserved remarks, the Raisi administration also left virtually nothing for the new government. On his first day in office, Pezeshkian had to borrow from the Khamenei-controlled foreign currency reserve to settle government debts to farmers.

While the shift toward a more moderate conservatism is being spearheaded by Parliament Speaker Ghalibaf, Pezeshkian has shown signs of aligning with hardliners to secure his position.